Electricity Meters Demystified: A Technical Guide to Metering Technologies

Electricity Meters Demystified: A Technical Guide to Metering Technologies

- Last Updated: December 17, 2025

Owon Technology

- Last Updated: December 17, 2025

Understanding the evolution and technical underpinnings of electricity meters is crucial for engineers, facility managers, and energy professionals. This guide provides a detailed examination of prevalent meter types, moving beyond basic functionality to explore their operational principles, communication protocols, and ideal application scenarios.

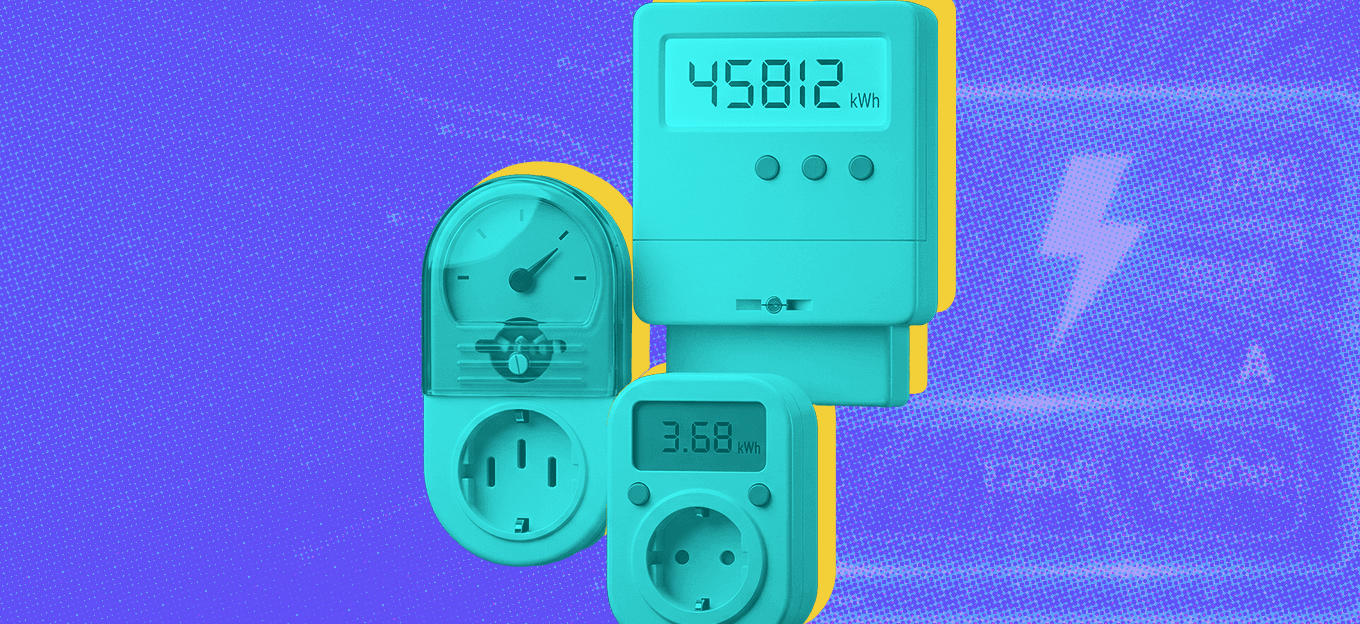

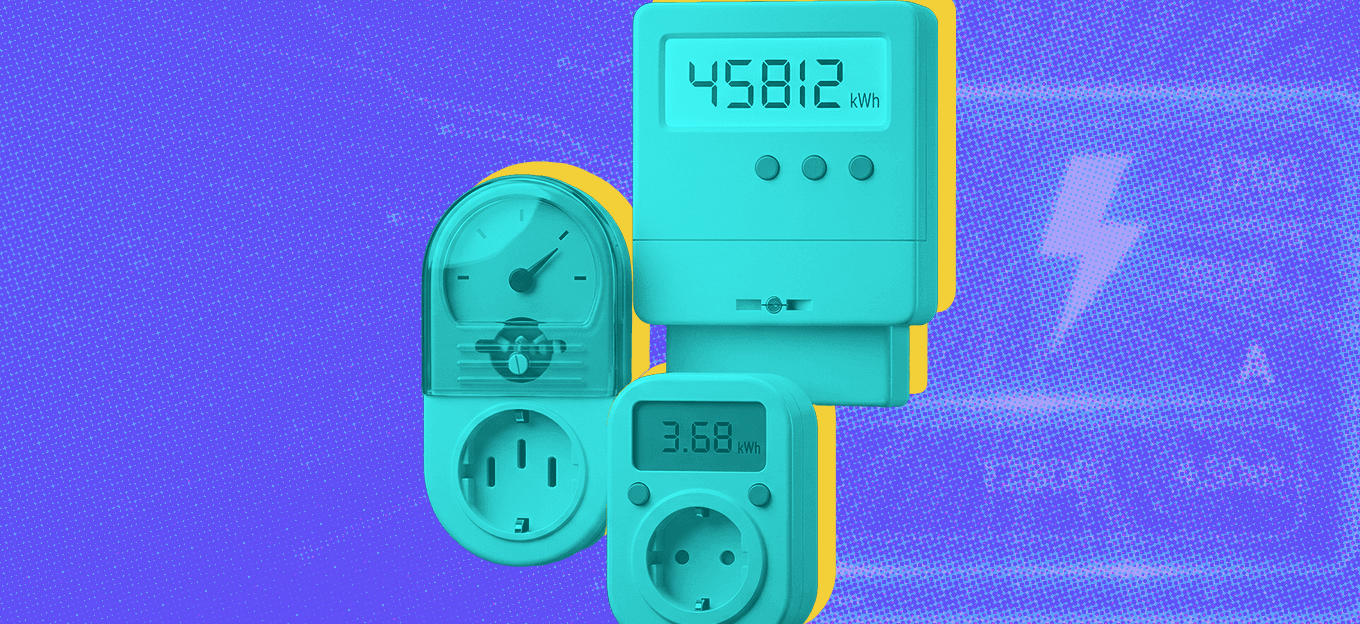

1. Electromechanical Induction Meter (The Analog Workhorse)

- Operating Principle: Based on Faraday's Law of Electromagnetic Induction. A voltage coil and a current coil generate magnetic fields proportional to the supply voltage and the load current, respectively. These fields induce eddy currents in a rotating aluminum disc, creating a torque that spins the disc. The rotational speed is directly proportional to the instantaneous power (Watts), and a gear train mechanism advances the dials to display cumulative energy consumption in kilowatt-hours (kWh).

- Key Components: Voltage coil, current coil, rotating disc, permanent magnet (for damping), and register dials.

- Accuracy & Limitations: Typically, Class 2.0 accuracy. Susceptible to calibration drift over time due to mechanical wear and friction. Lacks capability for time-of-use (TOU) metering or remote communication.

2. Electronic (Static) Energy Meter (The Digital Standard)

- Operating Principle: Utilizes solid-state components to directly sample voltage and current waveforms. This is typically achieved with dedicated metering chipsets or high-speed analog-to-digital converters (ADCs). The sampled values are digitally processed to calculate key parameters like Root Mean Square (RMS) values, active power (W), reactive power (VAR), and energy (kWh) using time-division multiplication or similar algorithms.

- Key Advancements:

- Superior Accuracy: Achieves Class 1.0 or better, with minimal long-term drift.

- Advanced Measurements: Capable of measuring parameters beyond kWh, including power factor, voltage sag/swell, and frequency.

- Time-Based Functionality: Internal real-time clock (RTC) enables TOU metering with multiple tariffs.

- Limitation: While highly accurate, a basic electronic meter functions as a "data logger" unless paired with a communication module.

3. Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) Smart Meter (The Data Gateway)

An AMI smart meter is an electronic meter equipped with integrated, bidirectional communication capabilities. It forms the endpoint of a network that enables real-time data transmission to the utility and, in many cases, to the consumer.

Communication Protocols and Topology

The choice of protocol significantly impacts the meter's application and data accessibility.

- RF Mesh Networks (e.g., Zigbee): Operate in the 2.4 GHz band (IEEE 802.15.4). Meters form a self-healing mesh network, relaying data for one another to extend range. Ideal for creating local area networks (LANs) within a facility, allowing for direct communication with sub-meters and in-home displays (IHDs). Offers robust connectivity for complex installations.

- Cellular (LPWAN, e.g., LTE-M/NB-IoT): Connects directly to cellular networks. Provides wide-area coverage without the need for building a dedicated network infrastructure. Best suited for geographically dispersed meters where LAN-based solutions are impractical.

- Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11): Leverages existing local area networks. Simplifies integration for residential and small commercial applications but may present challenges for network security and scalability in large, dense deployments.

Technical Capabilities of Modern Smart Meters

- High-Resolution Data Logging: Capture and report energy data at intervals as short as 1-10 seconds, enabling detailed load profiling.

- Power Quality Analysis: Monitor for events like voltage harmonics, transients, and interruptions.

- Remote Connect/Disconnect: Allow utilities to remotely control service.

4. Sub-Metering: Granular Energy Accountability

Sub-metering involves installing meters downstream of the primary utility meter to monitor specific loads, tenants, or systems. Technically, any meter type can be a sub-meter, but the full potential is realized with smart electronic sub-meters.

Application-Specific Considerations

- Tenant Billing (Multi-Tenant Units): Requires high-accuracy meters (typically Class 1.0 or better) with robust data logging to ensure billing integrity.

- Industrial Process Monitoring: May need meters with current transformer (CT) inputs to handle high currents and the capability to measure reactive power for assessing motor loads.

- Data Center & IT Loads: Demand meters with high sampling rates to capture the unique load profiles of switched-mode power supplies and cooling systems.

Technical Implementation: Devices like Zigbee-based power clamps exemplify modern sub-metering. They utilize split-core CTs for non-intrusive installation, measuring current (Irms) and, when paired with a voltage reference, calculating active power (W), power factor, and energy (kWh). Their wireless nature simplifies retrofitting into existing electrical panels.

Selection Framework: Matching Meter Technology to Application Requirements

Choosing the right meter requires a systematic analysis of technical and operational needs. Here is guidance for different scenarios.

For legacy basic billing applications, the electromechanical induction meter is the typical choice, with a focus on its accuracy class (e.g., 2.0).

For scenarios requiring Time-of-Use (TOU) billing, an electronic static meter should be selected, with key parameters being its internal Real-Time Clock (RTC) and the number of tariff registers.

As a building-level utility interface, an Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) smart meter (using cellular or RF communication) is suitable. The communication protocol and data reporting interval must be specified.

For tenant cost allocation, a smart sub-meter (e.g., Zigbee/Wi-Fi models) is appropriate. The core considerations are measurement accuracy (e.g., ≤ ±2%), the size of the matching Current Transformer (CT), and the device's data storage capacity.

For industrial load profiling, a smart meter with CT inputs is required, with a focus on advanced features like sampling rate and power quality metrics (such as harmonic analysis).

Key Technical Specification Questions

- What is the required measurement accuracy across the expected load range?

- What communication protocol aligns with the existing or planned network infrastructure?

- What data granularity (reporting interval) is necessary for the intended analysis?

- Are power quality measurements (e.g., Power Factor, Total Harmonic Distortion) a requirement?

Conclusion

The progression from electromechanical to smart meters represents a shift from cumulative energy accounting to granular, data-driven energy intelligence. For professionals, selecting the appropriate technology hinges on a clear understanding of operational principles, communication standards, and the specific data required to optimize electrical systems for efficiency, cost, and reliability.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

The State of Cybersecurity in IoT

Related Articles